Delia and Sohrab

Journeys of Filipino caregivers in America.

The medical training systems of the Philippines and the United States are subtly intertwined; it's a legacy that traces back to the colonial era. In this piece, Sofia Chiongbian Khu traces the journeys of Delia and Sohrab, two Filipino nurses from distinct backgrounds who built their careers by contributing to the American healthcare system. Their motivations were varied, but like many immigrants before them, they were shaped by a powerful cultural perception of America and the multifaceted promise it seemed to hold. Through their reflections, Sofia examines how the allure of the American dream shaped aspirations halfway around the world, and how those aspirations shifted with age and experience.

***

“From the start, I didn’t want to be a nurse. I wanted to be a lawyer.”

I’m on the phone with Delia Libarnes, a loquacious, leopard-print-wearing 81-year-old who came to the US to work as a nurse. She stayed for almost fifty years before deciding to return home to the Philippines, where she was born and raised and studied nursing.

I’ve known Delia my whole life. She’s my grandmother’s first cousin and close friend, and because she has spent her professional life caring for babies, she was present at my birth.

I wanted to understand why she even ended up in the US in the first place.

This question had always (until recently) seemed to have an obvious answer. It’s a fact of life that people want to immigrate to the United States. Of course, most people come here searching for economic or political stability. But Delia was always financially secure, if not wealthy. What pulled her to the States?

I learned that a mix of social and political factors played into Delia’s decision. I also learned that, for nurses trained in the Philippines, a particular kind of orientation to America was built into the foundation of their education.

Filipino Nurses

Most Americans are familiar with this pattern of migration—if you’ve interacted with the American healthcare system, there’s a good chance you’ve encountered a Filipino nurse. In 2019, 1 out of 20 nurses was Filipino, while Filipinos only comprise 1% of the entire American population.

It’s easy to find articles and books on this topic–see Catherine Ceniza Choy’s Empire of Care. According to Choy, the roots of Filipino nurse migration stretch back to when the “Philippine Islands” were an overseas territory of the United States, from 1899-1946.

The American colonial government set up hospitals and nursing schools with the same blueprint as their counterparts on the mainland. The curricula at these new nursing schools included English instruction in both proper grammar and colloquial English. They also followed the American model of the profession as established by Florence Nightingale’s reform efforts: nurses were to be well-behaved, well-kept and well-bred, and governed by strict, almost militaristic order and hierarchy.

Additionally, various funded programs and scholarships encouraged elite Filipinos, who were U.S. nationals, to pursue higher education in the United States. For nurses, this kind of American education and expertise was virtually required to reach a high position in the Philippines.

As the most successful Filipino nurses moved into administrative and leadership roles, they were sent to finish their training in the United States. And after the Philippines was granted independence in 1946, Filipino nurses continued to pursue what was seen as a valuable work-study opportunity in the U.S.

America, and anything to do with it, was the highest. In this sense, in the Philippines, nursing and America remained structurally intertwined, even after the nation gained independence.

How Delia Became a Nurse

But Delia had initially wanted to be a lawyer. She remembered a woman attorney that she used to see around town; young Delia wanted to be like her, doing something for the community.

Her father supported that dream, but her conservative mother did not. Delia has always been extremely talkative. Her mother worried that becoming a lawyer would encourage her to become even more outspoken, and that her daughter’s marriage prospects would diminish as a result.

Delia credits her father’s American education for his open mindedness, calling her mother’s mindset “more Spanish.” Her father attended Silliman University, an American missionary institution in the Philippines. His teachers were all American.

“Papa graduated from Silliman, so he was already–American, Western… Papa was more… [we had] more freedom.”

Delia eventually settled on nursing after learning one of her older cousins was pursuing it. She had an independent streak, and she loved a challenge. She also wanted to spite her mother, who let her pursue nursing, but made it clear that she didn’t think her daughter could rise to the challenge.

For Delia, nursing was a viable path to make an impact on the world. She did well, passed the Board Exams, and in 1966 headed to study and work in the United States as part of the Exchange Visa Program.

Established in 1948, the Exchange Visitor Program (EVP) allowed foreign professionals to study and work in the United States for up to two years; American professionals also participated in the program to work in countries like the UK, Denmark, and France.

According to Choy, the U.S. developed EVP to help counter anti-American Soviet propaganda during the Cold War, turning participating professionals into a kind of “ambassador” for America once they returned to their home countries. Initially, most participants were coming from or going to Europe, but by the late 60s, 80% were from the Philippines. A majority of participating Filipinos were nurses.

This was a relatively good deal for the United States. They got their ambassadors, and for their work these student-nurses received a stipend much smaller than the wages of an American nurse (granted, the EVP nurses were not U.S. Board certified as they intended to return to their home countries after the program).

I asked Delia why she chose to participate in the Exchange Visitor Program. She told me that was what everyone wanted to do at the time.

“You can learn more if you go to the States. And you’re young; you want something new… you want to be challenged.”

In Delia’s mind, EVP offered professional development to a level unavailable in the Philippines, as well as a sense of adventure and independence.

But why was the United States the place to learn? For nurses, the U.S. offered the same structure as the Philippines, with more opportunities; Americans created the Filipino system in their own image, so of course what was available in the States was better.

Choy argues that, as part of its colonial project, the United States posited itself as the paragon of civilization, establishing a policy of ‘benevolent assimilation’. Americans saw themselves as the paternalist stewards of an island nation full of undeveloped natives.

After the Treaty of Paris was signed, declaring the end to the Spanish-American war and the handover of the Philippines, Guam, and Puerto Rico, the occupation forces were directed to “announce… that [they] came, not as invaders and conquerors, but as friends, to protect the natives in their homes, in their personal and religious rights.”

This “civilizing mission” intertwined national development with personal and professional development on an individual level. As Filipinos strove to move up in the world, they strove towards this Americanness that was synonymous with modernity, progress, health, and individual freedom.

By the time that the Philippines gained independence in 1946 (on the Fourth of July, of all days), nursing, with all of its thoroughly American structures, was one of the clear paths to America–the physical place, as well as the idea of it: America as the modern, America as “the better life.”

Working in the United States

Participating in the Exchange Visitor Program, Delia spent one year at a maternity hospital in Jersey City, New Jersey, and one year at the Children’s Hospital in Washington, DC.

Her experience at the children’s hospital set her up for nearly thirty five years of working in pediatric intensive care units. Delia recalled treating young Vietnam war refugees in DC, and witnessing the Civil Rights movement up close.

Some nurses on EVP stayed beyond their allotted two years, mostly because the pay was so much better than in the Philippines, and some were under pressure to support their families back home.

As the daughter of small landowners, Delia wasn’t under such pressure. After her two years with EVP were up, she returned to the Philippines, glad to be back home.

She wasn’t planning to leave again; she told me that she didn’t want to go back to the States, and her mother didn’t want her to, either. That is, until dictator Ferdinand Marcos declared Martial Law in 1972. (It’s worth noting that Ferdinand Marcos’ regime was supported by the United States, due to his anticommunist stance).

This time, her mother pushed her out the door, unsure of what life would be like in the Philippines. Desperate to leave, she took the first opportunity she could get.

With her valuable EVP experience, Delia was recruited to a hospital in Lansing, Michigan. She stayed there working on an H-1 visa for one year, and then transferred to Cornell Medical Center in New York City. The hospital helped her obtain a green card, and then, eventually, citizenship. She remained there until her retirement in 2013.

She liked Cornell because she was challenged, but she was also free from the family and friends who judged her for not being quiet or marriageable enough.

In the early years, she faced the casual racism of doctors who assumed that she couldn’t speak English. A high-quality hospital like Cornell required its nurses to take several specialized exams, and she passed all of them, leapfrogging American nurses who studied at fancier schools.

She worked in the fast-paced, demanding environment of intensive care units for nearly forty years, caring for some of the wealthiest people in New York City and the world.

Her nursing work at Cornell was, as she sees it, the perfect setting for her self-actualization. She grew as a nurse, but also as a person: “It made me a strong person, because I was alone there,” she said. She lived alone, across the globe from most of her family, and still she found success and respect.

“I was able to do the things I wanted. I traveled the world,” she said.

Delia never married or started a family, so she often took shifts on holidays for the overtime pay. Her colleagues were grateful, and the money she made went to helping her nieces and nephews back home through school–two of whom are now nurses working in the US.

It also funded her travels to far corners of the world: Russia, Egypt, South Africa, Peru.

But Delia never really considered staying in the United States after retirement. When I asked her why, she sounded incredulous.

“Why? Because I want to enjoy my life here [in the Philippines]. I enjoyed my life when I was young there… [but] I want to stay in a house with a garden, [where] I don’t have to do everything. I want to enjoy my life!”

She is calling me from her ancestral home in Agusan del Norte, a province on the northern coast of Mindanao. Here, she tends a garden full of flowers and trees that her mother first planted decades ago. This is where she has lived since 2014.

At this stage in her life, where she is no longer craving adventure or a desire to prove herself in the world, life’s just better in the Philippines.

What is a good life? One where you can feel personally fulfilled, where you can feel that you have contributed to the world. It is also a life where you can feel at home, where you can wake up and tend to your garden and see your friends and family, and where friends and family can support you. For Delia, a career in the United States provided a piece of this, and her golden years in the Philippines will complete the puzzle.

While Delia’s family was not rich, her parents owned land and were able to send her and her four siblings to college; Delia’s earnings in the States helped send two of her nieces to nursing school, and eventually they also migrated to the United States. In this sense, Delia spread both the wealth and the aspiration of the American Dream.

Filipino Nurses Today

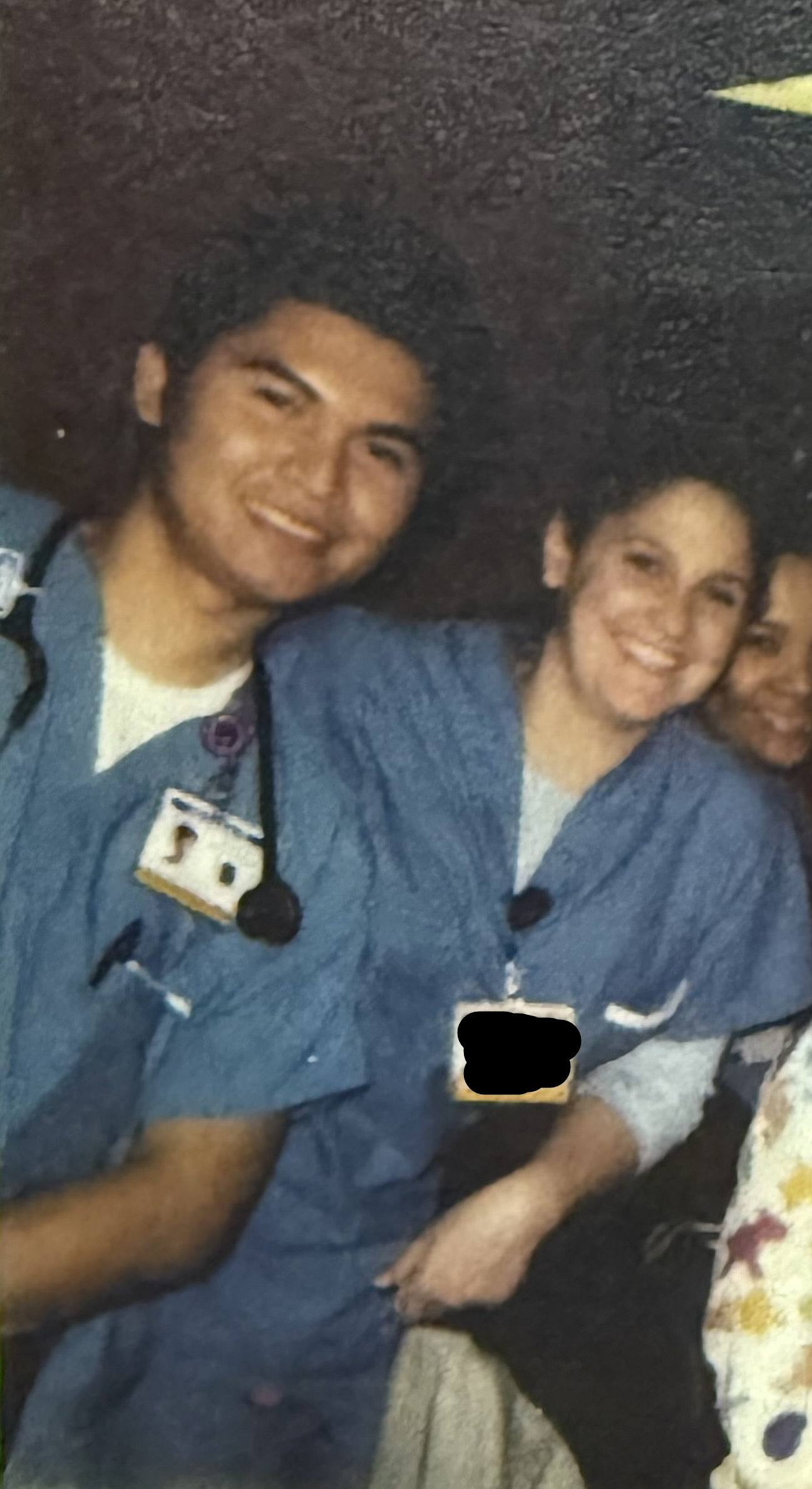

One of those nieces married another nurse from the Philippines who grew up 300 miles away from Delia and lived a very different life. His name is Sohrab Sardual, and today he is an accomplished nurse and the assistant director of the pediatric intensive care unit at Texas Children’s Hospital in Houston.

We talk at 11pm Houston time, a time that he suggests works for his schedule. He’s a busy person, evidently used to working late nights.

Sohrab grew up working class, in a region of the Philippines that is no stranger to armed conflict– the Zamboanga peninsula in southern Mindanao, in the city of Ipil.

Sohrab was a promising student; he received multiple scholarship offers to study subjects like math and physics, but his most complete offer was from his aunt, who was a nurse working in the United States. She offered to pay for tuition as well as books and housing… if he studied nursing.

So that’s what he did.

Looking back, it seems that healing was in his blood, though this took forms specific to the Philippine countryside: his mother was a midwife, and his grandfather a practitioner of traditional healing massage. Sohrab grew up accompanying them on their rounds, watching them tend to people in their community.

After studying nursing at Silliman University (Delia’s father’s alma mater), Sohrab became a flight attendant: the pay was much better than what hospitals were offering fresh graduates. Due to an economic downturn, he was laid off and turned back to nursing, eventually finding a position as a Masters student/teaching fellow at his alma mater.

During his graduate studies, he was able to participate in a summer institute in the United States, for which he was issued a student visa valid for five years.

Still, he tried to make his way as a nurse in the Philippines. He could only find per diem positions that paid him 50 pesos per day (just over a dollar a day based on the exchange rate at the time), roughly half of the average daily wage in Mindanao. There were so many people who wanted this kind of experience that he, and every other aspiring nurse, just had to take what they could get.

The final push was the kidnapping of his uncle, who survived and returned home. His advice to Sohrab? Leave Ipil since you can.

So Sohrab left home. He moved to Texas and lived with his aunt, the same person who sponsored his nursing education, and attended community college while he studied for the NCLEX and applied for jobs.

Twenty years later, he continues to live in Houston with his wife and two children. He retains a strong connection to the Philippines; he currently serves as the president of the Houston chapter of the Philippine Nurses’ Association of America (PNAA), which advocates for Filipino nurses and helps new arrivals settle into their new lives and jobs in the United States.

I asked him to tell me about the biggest problems that Filipino migrant nurses face today in the United States. Aside from leading new arrivals through the requisite cultural transitions, the PNAA provides legal assistance for Filipino migrants who are exploited by the system of nurse migration.

Over the past few decades, a whole industry has grown around recruiting nurses in the Philippines, matching them with American hospitals, and completing the paperwork so the nurses can work legally. Nurses can sometimes face exorbitant fees from the agencies to get their cases processed, and when they arrive, they find that their employers pay them much less than their coworkers who are American citizens.

Despite the fact that nurse-migration from the Philippines to the US is a well-trodden path, many Filipino migrant nurses still arrive here alone and unfamiliar with their surroundings–and therefore vulnerable. Networks like the PNAA are crucial. Perhaps it is this kind of safety net that reassures Filipino nurses who are pushed to migrate abroad, and keeps them coming to the United States over other places in the developed world. As of 2020, 240,000 Filipino nurses work abroad in countries like the UAE, UK, Singapore, New Zealand, and Australia, while the United States alone has nearly 150,000.

I asked him if he intends to return to the Philippines, or stay here.

Sohrab explained that he’d been discussing this lately with his wife. They had always thought they’d go back home. But Sohrab and his wife, Joanna, have two kids who are now in their teenage years.

“The kids are Filipino-American, but all they know is that they’re American. They would stay here, so this is where our family would be,” said Sohrab.

“We are now rethinking our retirement plans. Some of my friends are doing the same: I think we will have to stay here, if only for part of the year. Some people do six months in the Philippines, six months here to be with their family.”

He tells me the story of one retired nurse he knew. She had stayed in the States to be with her kids and grandkids until she became less mobile and needed more care. She didn’t want to be a burden to her family, so she moved back to the Philippines, where expenses–especially those like paying for a caregiver–are much lower. When she finally made the move in 2017, Sohrab and Joanna bought her house.

“I think we may go back when we need help. Because, in my head, we can do a lot more good in getting help in the Philippines. You can get working students, send them to school while [they help] you… your money will go further and you can help a lot more people.”

Sohrab is determined to continue giving, to do the best he can with what he has. This is one definition of the good life: to have enough to be able to give much. He spreads the wealth and experience he’s gleaned from the U.S.: sending home money as a student, organizing and advocating for newly arrived nurses as a settled immigrant, building the careers of the next generation of Filipinos as a retiree. He’s invested in both places, thoroughly loyal to both of the places that have become his home.

Legacy

The American dream continues on, if not so often spoken from the mouths of Americans themselves, it now trickles through the money and the stories sent back home by immigrants.

Delia came to the States in the prosperous post-WWII era. Though our country is a vastly different place now, with a shrinking middle class and a widening disparity between the haves and the have-nots, the American dream–its ideal, as well as its material manifestations–retains its spell over all who have called the U.S. home.

And it continues to mesmerize those who have never set foot on its soil. This middle-class peace is the envy of the world. I think this is because the American dream outlines the ultimate imagined existence for many: peace that is achievable for anyone who works hard enough and saves wisely enough.

Delia and Sohrab both went abroad for more than just themselves. They came at the explicit encouragement of their elder family members, people who wanted to guarantee their safety.

While working here, they dutifully contributed their efforts and found professional fulfillment, climbing the ladder to managerial positions at elite hospitals. They helped their families and other immigrants along the way. Each gave back with what they knew, what they had.

I think this is how the tale of America lives on. It’s the immigrants like Delia and Sohrab who carry it forth in the way they live and the stories they tell. I wonder, sometimes, what that tale will sound like a decade from now.

Images courtesy of Delia Libarnes and Sohrab Sardual.

Sofia is a Fellow in the Tusk & Quill Rotational Program.

All opinions expressed here are solely of the author and do not reflect the views of the author’s employer.

0

0

Featured Content

Stay up-to-date with our latest articles